BY PRASHANT KUMAR MISHRA,

ADDITIONAL GENERAL MANAGER,

SOUTH WESTERN RAILWAYS, HUBBALLI.

HUBBALLI (KARNATAKA) , 12 FEBRUARY 2023:

Opium was the major source of revenue for British Government in India; at its peak, it was the second largest source of revenue for East India Company after land. East India company exercised stringent control over the production and trade of opium, virtually transforming the farming economies of Bengal, Bihar and U.P into opium producing machines. – Opium Inc, Thomas Manuel Regulation VI of 1799 had prohibited all private cultivation of poppy. The peasant was forced to cultivate a specified amount and plot of land and to deliver its entire production, unadulterated, at the fixed government price to the agent. A peasant who did not sow poppy after certification was required to pay a punitive amount of three times the initial advance. (Richards, Indian Empire)

The Company reserved to itself the sole right of cultivating the poppy and of selling the opium. Any infringement of this jealously guarded right was promptly and inexorably punished by confiscation, fine,

imprisonment. All Government officials, police, native watchmen, and even the native landowners were obliged to assist in protecting the monopoly. The Company did not, however, engage directly in the cultivation. This was left to the ryots, or farmers. The Company’s portion of the actual business consisted in inspecting the land offered for poppy cultivation, making advances of money to the ryot, to whom a licence for cultivating so much land was granted; receiving and examining, packing and storing, the opium brought in; retailing it to the licensed vendors in Bengal, selling it wholesale for exportation at Calcutta. Not an acre of land could be sowed with poppy seed, without licence from the Company’s agent. Not a pound of opium in all Bengal but must be delivered to the Company’s depôt before it could become an article of merchandise. ( British opium policy and its results to India and China,1876)

The whole lot was publicly sold on set market days by auction to merchants, who exported rather smuggled it to China in a unique state sponsored smuggling operation. Public auction was conducted in Calcutta on the express condition that opium had to be immediately exported from India.

A spacious new opium godown was constructed on the Strand Road at Calcutta, capable of affording safe stowage for 30,000 chests of opium ; a new export shed on the customs wharf at Calcutta , measuring 300 by 50 feet, and 10 new temporary sheds adjoining the Custom House premises at Calcutta, for the storage of goods.- Moral Progress of India , for 1859-60.

” The Friend of India” had reported: -” The clear profit of the British government of India from the consumption of opium by the Chinese at the end of the official year, 1848-9, will be found to have fallen little short of three crores and twenty lakhs of rupees, or three millions, two hundred thousand pounds sterling, ($ 15,488,000. ) It is the most singular and most anomalous traffic in the world. To all present appearances, we should find it difficult to maintain our hold of India without it; our administration would be swamped by its financial embarrassments. “ British government of India earned net revenue of four crores thirty-two lakhs and seventeen thousands of Rupees in 1857-58. –East India progress and condition 1859-60 . Of total Indian revenue of 43.8 million pounds in 1861-62, receipts from opium contributed 6.35 million pounds, the second highest after land and forest, which had contributed 20.1 million pounds. Receipts from salt and customs were 4. 56 million pounds and 2.87 million pounds respectively. (Selections From Despatches Addressed to The Governments In India, by The Secretary Of State In Council, 1863)

Revenue from Opium after deducting all expenses was more than entire land revenue of Bengal.

While the East India Company was working like a drug cartel masquerading as a government, it took elaborate measures to stop smuggling of opium in the country.

Despite the rigorous checks at every stage, some quantity of opium produced could not be collected by company’s agents and was siphoned off. The method of disposing of the illicit opium was often to sell it to some enterprising individual, who undertook to collect a considerable quantity, and to send it down to Calcutta, or to the French settlement at Chandernagore, where it could be kept in safety until an

opportunity was found for shipping it to China and the Straits, or for disposing of it to the Chinese residents in the capital.

Chandernagore, a French settlement of just 2330 acres, was often a refuse for those who wanted to evade the British authorities in India. Chandernagore railway station was in British territories as French had put very stiff conditions for allowing East Indian Railways to come to their area, but city and surrounding area was an independent French settlement. Mughal emperor Aurangzeb had granted permission to French in 1688 to erect a factory in Chandernagore.

At Chandernagore there always seems sufficient of the disreputable element to keep them from drying up; and I can fancy that they might be worse off than in a place where cheroots may be had for next to nothing, where billiards appear to be indigenous, and where there is no compulsion to mix in respectable society. For the class in question, indeed, it is a real blessing — the existence of such a refuge as “The Boulogne of the East.”( The Ganges and the Seine by Sidney Laman Blanchard)

Collector of Hooghly had reported in 1828 that opium revenue was much interfered with by smuggling in French Chandernagore. The price there was said to be 5 to 7 tollas as against 3 tollas per rupee in English territory. French government had secured the right of receiving 300 chests of opium from British Government for trading every year on the condition of not engaging in the manufacture of opium in Chandernagore.

In 1740 Chandernagore had 4,000 brick houses, while Calcutta, the City of Palaces, had chiefly mud hovels : but Clive crushed the design entertained by the French of making Chandernagore the Metropolis of India.

Before the East Indian Railway was carried through the heart of the districts in which the poppy was cultivated, the illicit opium used to be sent down to Calcutta, sometimes in convenient parcels that a man could carry on his back, but more commonly by the country boats that navigated the rivers Ganges and Hooghly from Benares to Calcutta.

Those two thin strips of iron, representing the mightiest and the most fruitful conquest of science, stretched hundreds and hundreds of miles across the boundless plains, through the wild hills of Rajmahal, swarming with savage beasts, along the bank of the great river that could not be bridged.

There were the colossal viaducts, spanning wide tracts of pool and sandbank, which the first rains would convert into vast torrents.

When the railway was opened, the smugglers soon took advantage of it. A man with a large package, ostensibly of onions, secured in a covering of goatskin, took his seat at Patna in a third-class carriage, with his package under the seat, and in a few hours he and his opium arrived safely at Chandernagore or Calcutta, where he was welcomed by confederates.

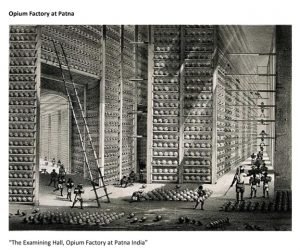

“In the Examining Hall the consistency of the crude opium as brought from the country in earthen pans was simply tested, either by the touch, or by thrusting a scoop into the mass. A sample from each pot

(the pots being numbered and labelled) was further examined for consistency and purity in the chemical test room.”

In order to stop this kind of smuggling, the Government paid a very high reward, far in excess of the actual value of the opium, to anyone who could detect and capture an opium -smuggler. A special railway police was organised and a network of informers and spies, who were earlier involved in smuggling, was created.

“The Inspector -General of Police has also been requested to take steps to arrange for the adoption of a good detective watch near Chandernagore, to prevent the illicit traffic under notice with that place; and the Excise Superintendent of Calcutta has been authorized to give special rewards to the informers and captors in Opium cases. The Board hope, with the Commissioner, that the disclosures made will, to some extent, put a stop to the trade in smuggled Opium.”(– Excise Administration Report for 1868-69)

The trains that arrived in the dark were usually patronised by the smugglers, and when the smuggler pulled out his package from under the carriage-seat, and stepped out on the station platform, he found himself accosted by some inquisitive policeman who wanted to know what was contained in the strong- smelling goat-skin package. The smuggler would probably offer a small sum of money to be let go, but that was of little avail, for there were other railway policemen looking on.

As opium had a strong and peculiar odour, the smuggler tried to conceal it by packing it with onions, and in a full-flavoured goat-skin. But the railway police soon learned to distinguish this special combination of smells, and a constable with a good nose could wind it at times before the door of the railway compartment was opened. (Opium Smuggling in India, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine ,1891)

Juland Danvers, secretary Railway Department in his report to the secretary of state for India described various ingenious methods used to transport illicit opium:

“Opium is smuggled in oil jars; the drug being packed between narrow receptacles for oil one passing through the middle of the jar and another just inside the covering. Opium is also sent in bags, described as containing gum , glue, & c.(Report To The Secretary Of State For India In Council on Railways In India 1859.By Juland Danvers, Esq).

The detected smuggler was apprehended and carried before a Calcutta magistrate and convicted. The men thus captured usually gave false names and addresses; but in some cases where their real name and the name of the village from which they came were discovered, measures were taken by the heads of the Opium Department to capture the rest of the local gang before they had time to learn the fate that had befallen their unlucky confederate.

“Several seizures of illicit Opium were effected during the year by Mr. Mackenzie at the Howrah Railway Station with the help of the Railway people. None of the fines were realized in these cases, the accused having all been imprisoned in default of payment. The Opium confiscated was 3 maunds and 2 seers in the aggregate”. ( Excise Administration Report for 1868-69)

The smugglers became alarmed at the captures being made in Calcutta, and for a time they tried the plan of throwing their packages of smuggled opium out of the windows of the railway carriages as the train passed along the borders of the French territory at Chandernagore.

This could easily be done in the dark, and the confederates who were expecting the packages were ready waiting to carry them off into the French settlement. But there was a very clever and active officer at the head of the Hooghly district, where the boundaries of British and French territory met, and as soon as he got wind of this new arrangement, he took measures to circumvent it.

Although the French police in Chandernagore had the reputation of being in the habit of giving their protection to smugglers and other delinquents who could afford to pay for it, they had one great merit,

for they were reasonable men and open to practical persuasion. If the smuggler paid 10s. to a French officer for protection, it was always possible, with the high rewards given for the detection of smuggled opium, to outbid the smuggler.

If a detective of the British Excise Department offered 15s. to the French police officer, the latter saw the force of the argument, and the pitiful fellow who had only paid 10s. was betrayed into the hands of the English Philistines.

The smugglers found that this form of conveying opium into French territory was not safe, and, at least for a time, they abandoned it. But there was still a chance of working the goods department of the railway, and in one or two large consignments of rice that were made from Benares and Patna, the smugglers managed to introduce some bags that contained a quantity of opium well surrounded by grain. But this plan often did not work out as respectable consignors and onsignees of grain were strongly adverse to it.

Whilst the grain was lying at the warehouse of the railway station awaiting delivery to the consignee, the smell of the opium would assert itself and betray its own secret. Moreover, some of the confederates were obliged to run a great personal risk by going to the warehouse to try and rescue the bags that contained opium; and after one or two failures, followed by convictions of the smugglers, this plan was dropped.

There remained the old plan of sending down the smuggled opium by country-boat, carefully packed and concealed under a cargo of onions, or tobacco, or hides, or anything that could mask or qualify the

smell of the opium. À country -boat took at least three weeks on its voyage down- stream from Patna to Calcutta, even when the river was in full flood.

The stream was very strong, but there was generally a high wind against the stream. The wind caught the upper part of the boat, which in size and shape was very like a floating hay – stack, so that the boatmen had often to come ashore and take to the tow -rope and tow down-stream in order to make any progress.

Meanwhile the consignment of this smuggled opium would become known to too many individuals, some of whom had no inclination to keep a secret, especially when a shrewd detective officer was tempting them with a good round sum to betray it. There was а a place called Saheb-gunge on the river Ganges, half- way between Patna and Calcutta, where all the country-boats were required to stop to give particulars of their tonnage and cargo. This detention was for purely statistical purposes, according to the theory of Sir George Campbell, Lieutenant Governor of Bengal who introduced it; but it tended to the great personal profit of the native subordinates, who had the power to stop, and to let go, each boat as it passed.

This was a favourite spot for the excise detectives, who could easily spot the smuggler with his cargo of onions and hides, beneath which packets of opium were concealed.

The detectives or informers never attempted to stop or to seize the boat and its cargo at this point, for reasons which were obvious. They only took care to identify the boat and to ascertain to what place it

was bound, and to whom the cargo was consigned. This could easily be ascertained from the papers which the captain or the supercargo of the crew was required to show for statistical purposes.

One great source of supply of contraband opium was in Nepal. The kingdom of Nepal was independent, and where its boundaries touched those of the British territory the Nepalese ryots were in the habit of cultivating the poppy without any licence or interference from their own Government. There was a departmental rule under which any Nepalese ryot could take the opium that he had manufactured, and receive for it the price of 5s. a -pound from the nearest opium agency of the British Government; but as there was a chance of making a much higher profit for himself by selling to smugglers and their confederates.

Formation of a special Railway establishment

Alarmed at the rising incidences of opium smuggling in trains, a special establishment was formed for the prevention of illicit traffic in opium by railway passengers, under the orders of Government No. 448, dated the 1st February, 1867, at a monthly cost of Rs. 130. Posts of one Sub-Inspector (50 Rs/month) and 10 Constables at 8 Rs per month were sanctioned.

As per intelligence reports received from detectives who had been smugglers of opium themselves, it appeared there were several persons in Calcutta, who every year sent their agents to Behar, after the season, to purchase opium from the cultivators. The latter, in an average season, reserved a surplus after delivering opium to the Government Officers of the Opium Agency. The demand from the

“ Assamees ” was regulated by the average produce of each field, ascertained from the Returns of a Koot Ameen ” who was deputed to survey each field, and report what the produce was likely to be. The smugglers stated that most cultivators had a surplus over the “ Koot ” which they sold privately.

A quantity of opium was sent down by rail, but a larger quantity was said to find its way to Chandernagore and Calcutta by water in boats. Some of the boats were ostensibly laden with onions beneath which the opium was concealed. The strong scent from the onions prevented the smell of opium being easily detected. In other boats, the bamboos – especially those used for the roof, -had their knots beaten out, and each bamboo was filled with opium. Others, again, had bottles and hollow Bamboos, filled with opium, fastened to nails at the bottom of the boat, under water. A quantity of opium, it was said, was also brought down in indigo-boats from Tirhoot and Purneah.

The two informers, Shib Churn Mullah and Gokool Pershaud Parrah , who were engaged as detectives, were well acquainted with the men who sent down opium by water. Police were placed on the watch, but either because the alarm had been given , or the boats evaded the detectives, the Police were not successful in intercepting any boats thus laden. It was also ascertained that a quantity of opium was sent every year on bullocks ostensibly loaded with jaggery, by the Gyah road through Hazareebaugh, Beerbhoom, Bancoorah, and Burdwan, to Mohurbunje in the Balasore District. There were two detectives, set apart to watch for this opium; but they did not succeed in intercepting it. ( Report on The Police of The Lower Provinces of The Bengal Presidency for The Year 1867)

The Extra Assistant, Baboo Nobokisto Ghose, worked the temporary Establishment for three months, while prosecuting the drugging cases at Patna, in addition to his other duties ; and every credit was due to him for organizing and for the information which has been collected. During the last two months the Extra Assistant Baboo Ishree persaud Singh had charge of the party. (papers relating to opium question,1870)

Twenty-three cases were prosecuted before the Magistrates of Patna, Monghyr, and Bhaugulpore. Six cases were unsuccessful, while convictions were obtained in seventeen. In the latter, the fines inflicted on the accused parties amounted to Rs.2,165. The total quantity of opium confiscated was 1 maund, 16 seers, and 12 chuttacks ; the value of which, at the prescribed rate of 16 Rupees per seer, was Rs. 908.

The expense of the Establishment for five months had been Rs. 650. It was reported by IGP lower provinces that the East Indian Railway had sent in bills on account of railway passes for the detectives employed on the line to the extent of Rs. Rs. 400. Total return was 1990 Rs 8 Annas(value of opium Rs 908 and half fines 1082 Rs and 8 Annas) so still there was a profit to Government of Rs. 940 and 8 Annas.

“I may observe that the East Indian Railway have charged the usual passenger rate for these passes; but there is no doubt the presence of the detectives on the line prevented many of their servants from engaging and aiding in these illicit transactions; it would be a question, therefore, whether they ought not to travel free. “

He suggested that should it be considered necessary to repeat the experiment of the temporary establishment next year, there should be two Head Constables and eight Constables on the line of the East Indian Railway Company, two Head Constables and eight Constables on the Gya and Grand Trunk Roads, and two boats on the Ganges with a Head Constable and four Constables attached to each. The entire force should be placed under the charge of a Sub – Inspector. – Letter No. 5781, dated 17th September 1867. From — Lieut. – Colonel J. R. Pughe, Inspector. Genl. of Police, Lower Provinces, to The Officiating Secretary to the Government of Bengal.

The employment of the Establishment had answered its purpose as a preventive measure. Very little opium that year had found its way down the line of the East Indian Railway Company. It was generally brought in small quantities, in fact as much as a single passenger could conceal about his person or in a bundle, which accounted for the seizures in each case being small. But no sooner was it known that it was no longer safe to make use of the railway line as a means of transit, then the transmission of opium down the line entirely ceased. In judging, therefore, of the result of the operations of the temporary Establishment, it was only fair to take into consideration its preventive effects on the illicit traffic in opium by railway passengers.

- D. Robertson Commissioner of Customs, Salt and Opium in his letter to the acting Chief Secretary to the Government, also reported that-

“I do not consider any one desirous of smuggling opium would adopt the railway as a means of transport to the destination from whence he intended to despatch it, as the packages would have to run the risk of discovery by one or other of the numerous European officials employed on the railways, and because it would be much more hazardous than conveying it to the coast by quieter and less frequented routes,

and where he would stand a better chance of buying himself and his contraband wares off in the event of detection. “

The most important work subsequently done in connection with opium-smuggling was the breaking up of the notorious gang of Benares opium-smugglers, known as sát bhaiyas ( seven brothers), most of whom were convicted and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment.

For some time past it was known by the Excise Department that these smugglers were bringing opium into Calcutta; and with a view to mislead the Excise detective staff, they used to despatch it to the several East Indian Railway parcel stations at Howrah, Fairlie Place, Chowringhee, and Harrison Road or to Sealdah. The opium was consigned as tobacco, a small quantity of tobacco being placed over the opium to suppress the smell of the drug. It was after months of hard labour and very careful and intelligent watching that the Excise officers were able to trace out the several depôts of this notorious gang and to discover the members thereof. (Report on the Administration of the Excise Dept. in the Lower Provinces,1904-05)

“Baburam Kalwar, son of the aforesaid accused, Dwarka Kalwar, imported a large quantity of abkari opium from Ghazipur in railway parcels despatched to the Chowringhee Branch Parcel Office of the East Indian Railway. These parcels were sent in the names of three different consignees, known to be private enemies of Dwarka Kalwar, with a view to throw suspicion upon them in case delivery of the parcels was not easily secured. Baburam Kalwar, on conviction, was sentenced to four months’ rigorous imprisonment and to a fine of Rs. 200. The quantity of opium seized was nine seers.-

The house of Kasi Nath Benia, known as a scribe employed by the above-named notorious gang, was searched; but instead of getting any opium the Excise officers recovered a railway receipt in the name of the accused. The parcel covered by this receipt was ultimately found in the Fairlie Place Branch Office of the East Indian Railway, and on being opened was found to contain 2 seers of opium.

One Zanalal Sadhu, who was a member of a gang of Mirzapur opium- smugglers, was arrested at the Howrah Railway Station with a large quantity of Mirzapur opium (15 seers) in his possession. He was found carrying the drug in a bag of rubber sheeting with a view to suppress the aroma of opium. He, onconviction, was sentenced to a fine of Rs. 1,000, or, in default to six months’ rigorous imprisonment. (Report on the Administration of the Excise Dept. in the Lower Provinces,1904-05)

The active measures taken by Government and Railway companies would virtually put an end to smuggling of opium by Railways, except for some sporadic incidences; but Railways were preferred carriers for transporting the official opium chests. EIR carried 7446 Tonnes of opium in 1871, which would rise to 9599 Tons in 1881, earning receipts of 2,36,384 Rs. – Administration report on the Railways in India 1882-83

“Indian Railways often deal in strange freights, and the East Indian is no exception to the rule. Special train loads of nothing but wagons full of opium, for example, are probably peculiar to India. The manufactured drug is carried from the Government factories in faraway Patna or Ghazipore to Calcutta, whence it goes by sea to distant China, and it may here be mentioned that the value of a consignment of opium is so great and its constitution so tender that should there be but the sign of a cloud in the sky on the day arranged for its despatch, the loading is deferred until all conditions are favourable.” ( The Railway Magazine March, 1906 . The East Indian Railway. By G. Huddleston)

Advertisement:

Add Comment